Introduction

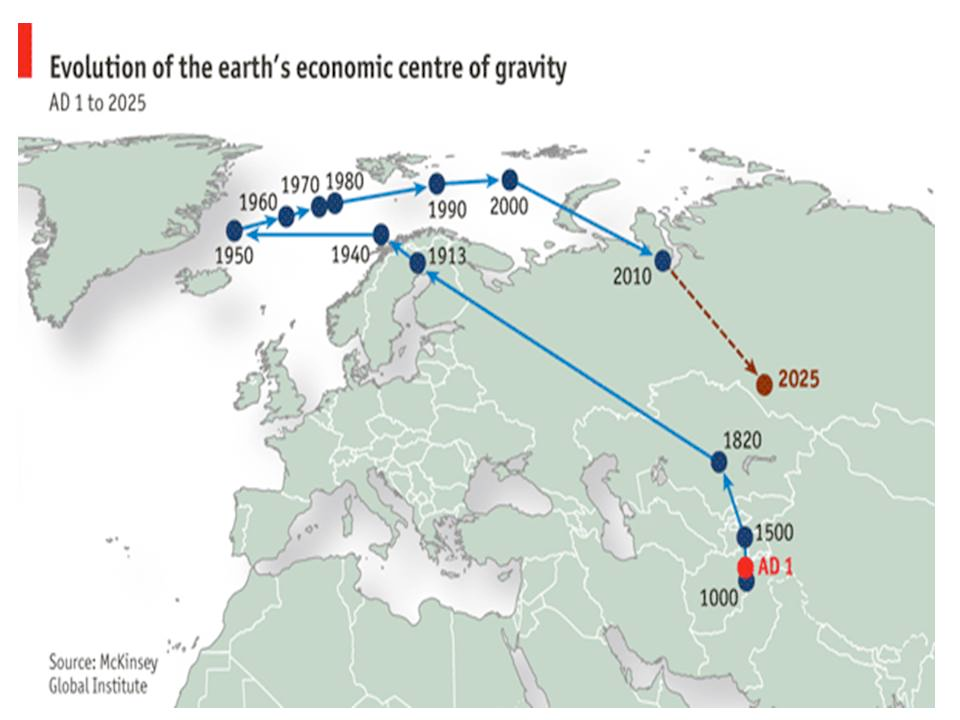

The global economic center of gravity, as illustrated in the McKinsey Global Institute’s mapping from AD 1 to 2025, has traversed a remarkable journey across continents, reflecting the rise and fall of civilizations, empires, and economic systems. This paper argues that technological innovation stands as the primary driver of these shifts, propelling economic dominance to regions that pioneer transformative technologies—whether in agriculture, industry, or digital systems—while enabling those societies to leverage trade, political stability, and resource control. Over the past 5,000 years, from the ancient river valleys of Mesopotamia to the industrial heartlands of Europe and the emerging technological hubs of East Asia, technological breakthroughs have consistently reshaped economic power. Looking forward, we predict a continued eastward shift over the next 200 years, with Asia, particularly China and India, reclaiming economic preeminence by 2225, driven by their leadership in artificial intelligence, renewable energy, and global supply chain innovation.

This thesis integrates historical evidence with economic theory, drawing on peer-reviewed studies, institutional reports, and classical and contemporary analyses (e.g., Landes, 1998; Acemoglu & Robinson, 2012; McKinsey Global Institute, 2019). By examining the interplay of technology, politics, and trade, we aim to elucidate why economic power migrates and how it might evolve in the coming centuries.

Historical Analysis: Technological Innovation as the Engine of Economic Shifts (3000 BCE to 2025 CE)

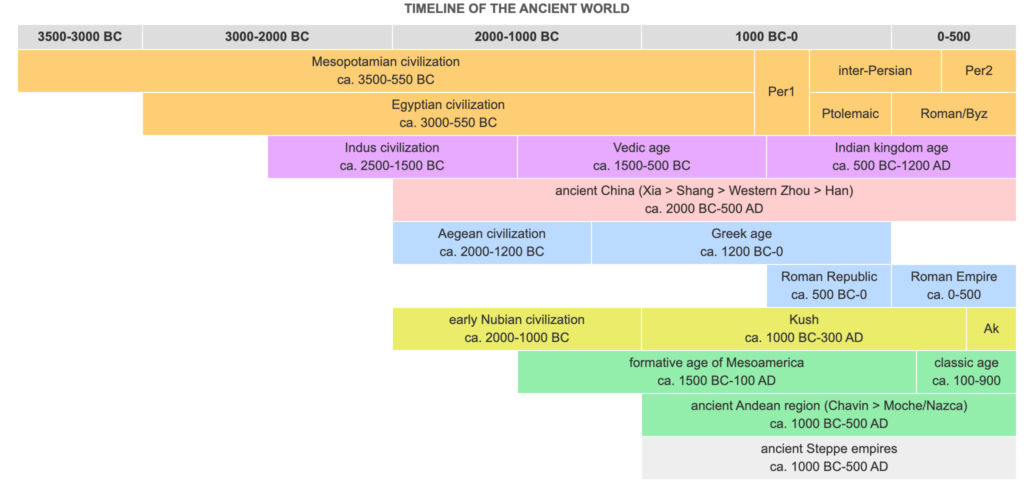

The economic center of gravity’s movement over millennia can be traced to regions where technological innovations catalyzed productivity, trade, and societal organization. Around 3000 BCE, the economic hub likely resided in Mesopotamia, where the invention of irrigation systems, the wheel, and early writing (cuneiform) enabled surplus agricultural production and trade networks along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers (Kramer, 1963). These innovations underpinned the rise of city-states like Uruk, establishing the region as an economic powerhouse.

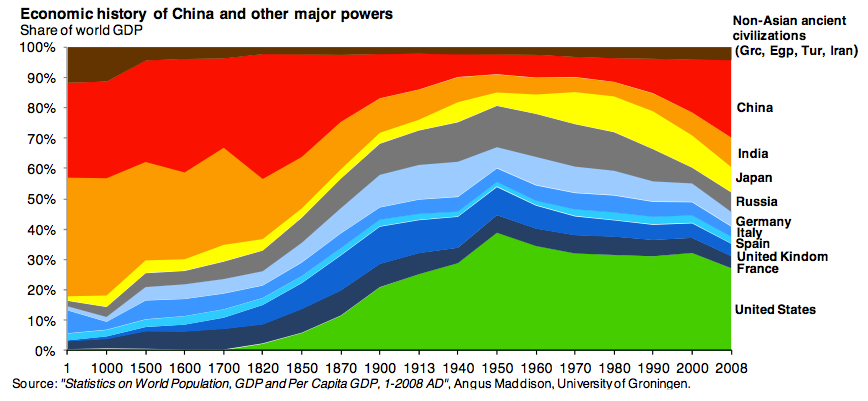

By 1000 CE, as depicted in the McKinsey map, the center had shifted eastward to India and China, driven by technological advancements such as the plow, papermaking, and the compass. The Tang and Song dynasties in China, for instance, leveraged gunpowder, printing, and maritime technologies to dominate East Asian trade routes, while India’s cotton textile innovations fueled global commerce via the Silk Road (Needham, 1981). These innovations not only enhanced productivity but also attracted political and military control, reinforcing economic dominance.

The westward shift beginning around 1500 CE coincided with the European Renaissance and the Industrial Revolution. The printing press (c. 1440), navigational improvements (e.g., the astrolabe), and later steam engines and mechanized production transformed Europe into the economic epicenter by 1820 (Landes, 1998). Britain’s dominance in the 19th century, marked by its industrial technologies and colonial trade networks, exemplifies how technological leadership—coupled with resource control—solidified economic power.

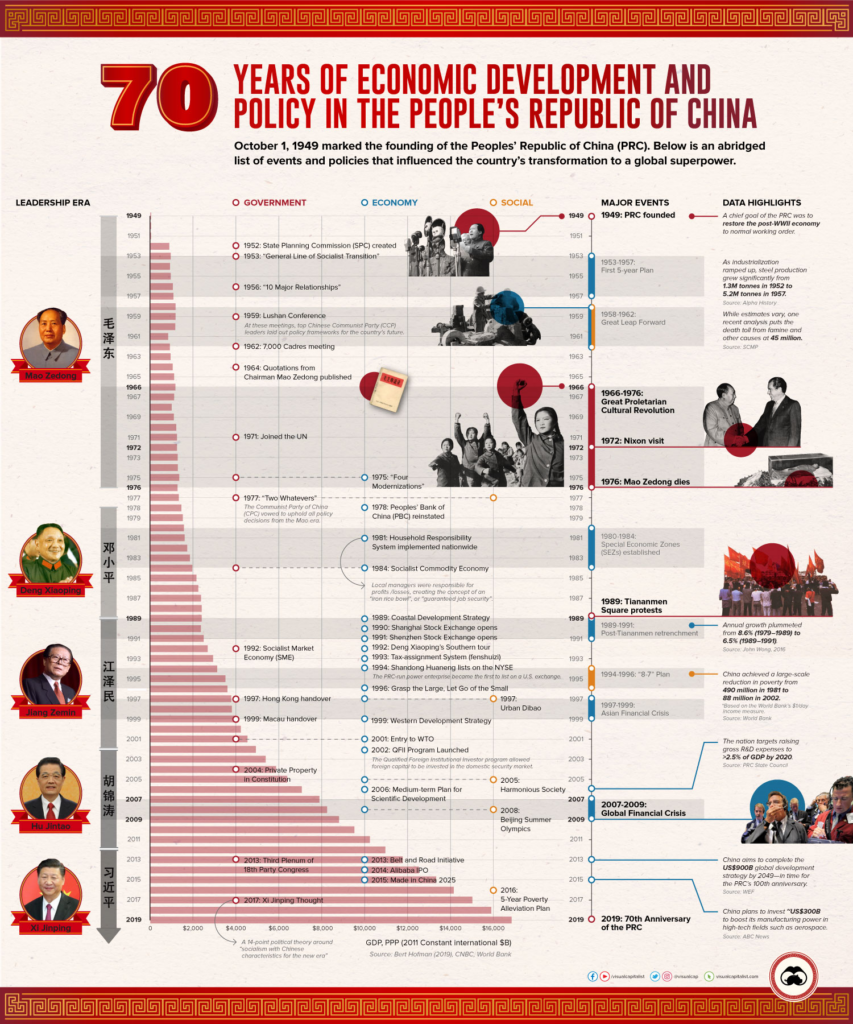

By the 20th century, the United States emerged as the new center, propelled by electricity, automobiles, and, later, information technology. The McKinsey map’s trajectory from 1950 to 2025, stretching toward East Asia, reflects China’s rise, driven by its adoption of digital technologies, manufacturing automation, and renewable energy systems (McKinsey Global Institute, 2019). This pattern underscores our thesis: economic power follows regions that innovate technologically, adapting to global demands and outpacing competitors.

Correlation with World Events

Technological innovation does not operate in isolation; it interacts with political upheavals, wars, and trade dynamics. The fall of the Roman Empire (c. 476 CE) fragmented Europe, shifting the economic center eastward as China and India maintained technological and trade superiority during the medieval period. Conversely, the Age of Exploration (15th–17th centuries) saw European powers, armed with navigational and military technologies, colonize resource-rich regions, redirecting the economic center westward (Pomeranz, 2000).

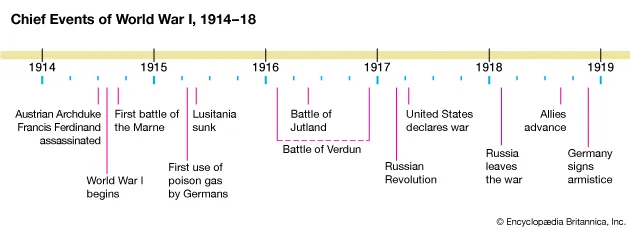

World wars in the 20th century further illustrate this dynamic. The United States’ technological edge—spanning aviation, nuclear energy, and computing—enabled its postwar economic dominance, as Europe recovered from devastation (Kennedy, 1987). Today, geopolitical tensions, such as U.S.-China trade disputes, hinge on technological leadership in semiconductors and AI, signaling Asia’s potential ascendancy.

Social, Political, and Philosophical Implications

Why do some societies sustain technological leadership longer than others? Institutional stability, cultural openness to innovation, and education systems play critical roles. The European Enlightenment fostered scientific inquiry, leading to the Industrial Revolution, while China’s historical bureaucracy, though initially innovative, became rigid, contributing to its stagnation by the 19th century (Mokyr, 1990). Conversely, modern East Asian states, such as South Korea and Singapore, have prioritized education and R&D, sustaining technological advancement.

Philosophically, societies valuing meritocracy and adaptability—traits often linked to technological progress—tend to maintain economic dominance. However, complacency or resource over-reliance can precipitate decline, as seen in the Spanish Empire’s fade after its silver-based economy stagnated (Chaunu, 1979).

Future Projections: The Eastward Return (2025–2225 CE)

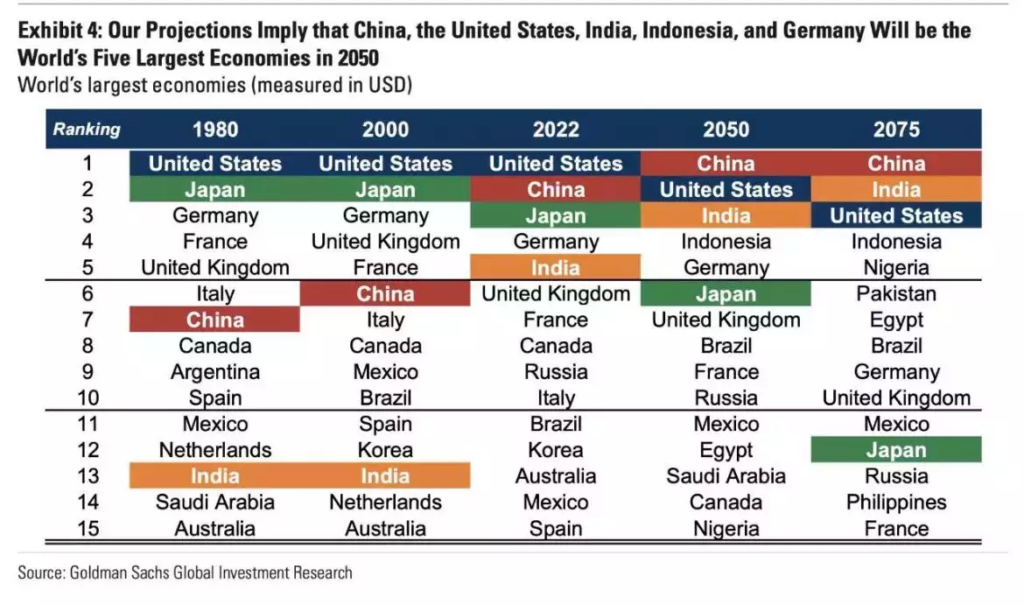

Based on historical patterns, we project the economic center of gravity will continue its eastward migration over the next 200 years, driven by Asia’s technological leadership. By 2050, China and India’s investments in AI, quantum computing, and green technologies—already evident in 2025—will likely solidify their dominance, as McKinsey and IMF reports suggest (International Monetary Fund, 2023). Asia’s population, skilled workforce, and control over critical supply chains (e.g., rare earth minerals) will further this trend.

By 2100, we anticipate the center settling near East Asia, with China and India collectively accounting for over 50% of global GDP, driven by their leadership in autonomous systems and space technologies. This projection aligns with demographic trends, as Asia’s population remains a global economic engine, contrasted with aging populations in the West (United Nations, 2022).

By 2225, the center may stabilize in Southeast Asia or India, reflecting a “return to the East” reminiscent of 1000 CE. This shift will depend on continued technological innovation, political stability, and the ability to navigate climate change challenges—factors Asia is well-positioned to address, given its current R&D investments and renewable energy adoption.

Conclusion

The global economic center of gravity’s movement over 5,000 years reflects a consistent pattern: technological innovation drives economic power, enabling regions to dominate trade, resources, and institutions. From Mesopotamia’s irrigation systems to China’s AI advancements, technological leadership has been the linchpin of economic dominance. Looking ahead, Asia’s trajectory suggests a reversal to its historical preeminence by 2225, contingent on sustaining innovation amidst global challenges. This analysis, grounded in historical evidence and economic theory, underscores the enduring interplay between technology and economic power, offering a roadmap for understanding humanity’s economic future.

References

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2012). Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty. Crown Business.

Chaunu, P. (1979). European Expansion in the Later Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press.

International Monetary Fund. (2023). World Economic Outlook: A Long and Difficult Ascent. IMF Publications.

Kennedy, P. (1987). The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers. Random House.

Kramer, S. N. (1963). The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character. University of Chicago Press.

Landes, D. S. (1998). The Wealth and Poverty of Nations: Why Some Are So Rich and Some So Poor. W.W. Norton & Company.

McKinsey Global Institute. (2019). Globalization in Transition: The Future of Trade and Value Chains. McKinsey & Company.

Mokyr, J. (1990). The Lever of Riches: Technological Creativity and Economic Progress. Oxford University Press.

Needham, J. (1981). Science and Civilisation in China (Vol. 4). Cambridge University Press.

Pomeranz, K. (2000). The Great Divergence: China, Europe, and the Making of the Modern World Economy. Princeton University Press.

United Nations. (2022). World Population Prospects 2022. UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

Follow me on IG@AliMehediOfficial